Clinical Research Ethics: The Foundation of Trustworthy Trials

Introduction to ethics in clinical research

Ethics represent a fundamental pillar of clinical research, ensuring the protection of participants’ rights, promoting scientific integrity, and maintaining public trust. As we will explore in this article, many of these safeguards have been set forth after historical instances involving particularly unethical treatment of human subjects. Ethics is defined as “a set of moral principles for right conduct,” and within clinical research, ethics is concerned with the fair and correct treatment of participants.

Upholding ethical standards in clinical research involves adhering to a set of principles and guidelines that prioritize the well-being and autonomy of study participants while minimizing potential risks posed by the study. These ethical principles serve as a sort of ‘moral compass’ for researchers, sponsors, institutional review boards (IRBs), regulatory agencies, and healthcare professionals to critically assess whether a clinical trial is prioritizing and appropriately ensuring the safety and fair treatment of participants.

Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines set forth by the ICH provide detailed recommendations on ethical clinical trial conduct which address all aspects of trial operations and data handling. It is then national/regional regulatory agencies, like the FDA in the US and the EMA in the EU, who ultimately enforce ethical standards in each region.

Transparency and accountability are two other core components of ethics in clinical research. Transparency involves the honest and open reporting of results – whether positive or negative – which boosts public trust in clinical research and ensures that results can contribute to the growing body of clinical knowledge. Accountability entails assuming full responsibility for adhering to ethical conduct throughout all phases of a trial in order to uphold research integrity.

What are the main ethical issues in clinical trials?

Although there are guidelines in place, clinical researchers still run into ethical obstacles when identifying research directions and designing studies. In fact, that is part of the reason why ethical guidelines exist - to serve as a reference for navigating these ethical questions.

Ethical factors weigh into almost every clinical decision, and these choices often involve trade-offs between upholding ethical treatment standards and performing more rigorous scientific tests of an intervention, since human subjects can only be ethically exposed to a certain degree of risk.

Informed consent is a topic that receives a lot of attention within discussions on ethics in clinical trials. Participants must have – and be able to confirm that they have – sufficient understanding in order to make an informed decision about participating. We’ve written in detail about informed consent in another article. The key point here is that ethical treatment begins with guaranteeing that the subject is fully and completely aware of what the study involves and requires of them, including an explicit acknowledgement of the risks it carries. The informed consent process must be clear and free of any sort of coercion, and consent to participate must be entirely voluntary. Usually, informed consent will involve a verbal discussion to confirm the patient’s understanding, and the patient should be made aware that they have the fundamental right to leave the study at any time, for any reason.

Confidentiality and privacy concerns also arise, both for patients themselves and for their data. Due to the sensitive nature of data collected during clinical research, i.e., personal health information (PHI), specific steps must be taken to ensure secure data handling practices.

Scientific misconduct is another risk to the integrity of clinical trials. Fraudulent practices such as falsifying or fabricating data, selective reporting of results, or plagiarism are also considered unethical, as they compromise the reliability of individual studies but also carry significant risks related to approving drugs and making patient care decisions based on falsified or exaggerated results.

Other unethical practices in clinical research can have, as we’ve unfortunately seen in the past, disastrous consequences for participants and public trust in science. Abuse of vulnerable populations, inadequate oversight by ethics committees or regulatory bodies, conflicts of interest, and inadequate monitoring/compliance with ethical guidelines all constitute unethical conduct. While today’s standards of accountability are much stricter and there are potentially severe penalties and consequences for sponsors, this was not always the case..

Clinical research ethics history: Lessons learned

The current landscape of relatively stringent clinical research ethics has been shaped by significant events that prompted important changes in ethical standards. One such infamous event was the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, conducted between 1932 and 1972, wherein the already available treatment was withheld from almost 400 African-American men with syphilis, who also had not given informed consent. This study represented a gross violation of ethical principles and constitutes abuse of a vulnerable population. Although extremely ugly, this situation eventually led to a fundamental shift in ethical guidelines (at the global level), and specifically influenced the development of regulations on informed consent requirements for research studies involving human subjects.

Many more lessons have been learned from past trials – both successes and failures – and have driven improvements in mechanisms for protecting human subjects involved in medical research. These improvements are still ongoing, but below we will explore some of the principles that are currently widely adopted for guiding ethics in clinical research.

Clinical research ethics frameworks

In the next sections, we explore two different sets of principles for clinical research ethics. Neither of the two definitions is a universal standard, but they are amongst the most commonly applied and referenced guidelines regarding ethics in clinical trials. Other codes and guidelines that have been highly influential in the development of modern medical research ethics include the Belmont Report, the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Nuremberg Code. US 45 CFR part 46 subpart A, or the Common Rule, is a set of regulations set forth by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which was largely based on the Belmont Report. Formally called the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, the Common Rule has the principal aim of protecting human subjects in research – both biomedical and behavioral – supported or conducted by HHS.

Regardless of the exact wording or categorization, ethical standards in clinical research have largely been compiled from similar values and ideas, and essentially share the same end goals of safeguarding patient well-being and ensuring that clinical studies are relevant, valid, and of high quality. The different structures of ethical principles are meant to provide a foundation for ethical decision-making in clinical research, guiding researchers, sponsors, institutional review boards (IRBs), and other stakeholders in upholding ethical standards throughout the conduct of medical research studies.

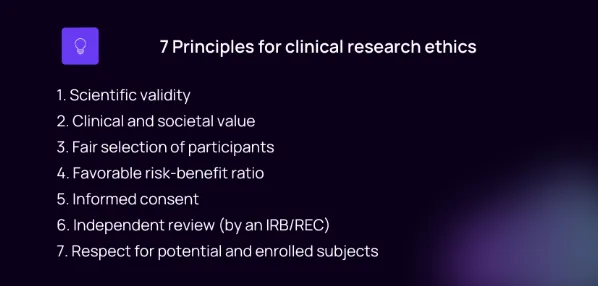

7 principles guiding clinical trial ethics

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center has aggregated ideas from influential publications and regulations regarding ethics in clinical trials to set forth the following 7 principles for clinical trial ethics[1]:

1. Scientific validity

Clinical trials should be based on a scientifically rigorous design, producing reliable and valid data that contributes to scientific knowledge. Exposing participants to risk for studies that are not robust in their design is unethical since such studies are unlikely to produce valid and useful results.

2. Clinical and societal value

Trials should address clinically relevant questions that have the potential to improve real patient health outcomes or advance public health. These questions should be significant enough to warrant asking participants to assume risks to answer it.

3. Fair selection of participants

The selection of participants should be done fairly, avoiding any form of discrimination or undue exclusion based on characteristics such as age, gender, race, or socioeconomic status, unless there is an explicitly increased risk in a certain population. Selection should be based on answering the questions “who needs to be included in the study in order to answer the research question?” and “who might benefit from the results?” Supporting diversity in study populations is another aspect that deserves particular attention, as it improves the generalizability of results and aims to promote equal access to research opportunities.

4. Risk-benefit ratio

Ethical trials involve careful consideration of the risks to study participants and the potential benefits of answering the research question. The potential benefits should outweigh or at least be proportionate to the risks involved. Some level of uncertainty about risks is assumed in clinical research, and tends to be higher for early-phase studies, but the risk should be offset by significant potential for eventually improving health outcomes. Patients assume this risk as part of their consent to participate, and while they may experience benefits at a personal level, receiving care or treatment is not the primary goal of clinical trials.

A thorough risk-benefit analysis should be conducted during the planning phase of research, and this analysis will also be considered (or replicated) by ethics committees while making decisions about whether to approve a trial.

5. Informed consent

Participants must provide informed consent voluntarily after receiving clear information about the nature, purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, alternatives, and any potential conflicts of interest associated with the trial.

Obtain informed consent from participants after providing clear and comprehensive information about the nature, purpose, procedures, potential risks, anticipated benefits, and alternatives related to the study. This enables participants to make autonomous decisions based on sufficient knowledge.

6. Independent review by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Research Ethics Committee (REC)

Ethical standards in clinical studies are upheld in a large part through oversight by an independent third party. Study protocols and all communications and promotional material are reviewed by an independent review board (IRB) in the US, or a research ethics committee (REC) in the EU and the UK. These panels consist of multidisciplinary experts who assess the trial's scientific merit, participant safety considerations, and adherence with ethical guidelines such as those set forth in GCP.

7. Respect for potential and enrolled subjects

Individuals who are approached for participation in a clinical trial should be treated with respect from the very first contact, even if they decide not to participate. Respect includes listening to their concerns and respecting their decision to participate or not, as well as respecting their privacy and keeping their personal information confidential through good data management practices. It extends to keeping them up to date about any changes to protocol or emerging findings that might affect their choice to remain in the study, and respecting their right to leave the trial at any moment. This aspect also encompasses strict safety monitoring in order to respond promptly to any potential adverse events or safety concerns. Finally, being transparent by explaining the results of the study is another form of respecting participants by making sure they see the results of their contribution.

What are the 4 pillars of medical ethics in research?

A different categorization of 4 principles for ethics in clinical research was set forth by Beauchamp and Childress in a 1989 publication, which has also since been adopted extensively:

1. Autonomy

Researchers must respect the autonomy of individuals and their right to make informed decisions about participating in research studies. This principle emphasizes the importance of obtaining voluntary and informed consent from participants without coercion or manipulation. It also emphasizes their right to withdraw from the trial at any point.

2. Non-maleficence

The principle of nonmaleficence requires that researchers prioritize the avoidance of harm to participants. Trial sponsors and clinical researchers must take all necessary precautions to minimize risks and ensure participant safety throughout the entire course of the study.

3. Beneficence

Beneficence describes the active promotion of the well-being and interests of research participants. Thus, in addition to minimizing potential harms, researchers should strive to maximize potential benefits to participants in order to achieve a favorable risk-reward balance. Disseminating study findings in an accessible manner so that participants can benefit from the knowledge generated through their participation is one way to ensure beneficence in research. In general, patient centricity provides a good conceptual framework for understanding how to prioritize the well-being and direct experience of research participants.

4. Justice

The principle of justice addresses the aspect of fairness in the distribution of both the potential benefits and the burdens associated with participation in research studies. Researchers are meant to ensure equitable selection criteria for inclusion in the study, avoiding any form of undue discrimination or exploitation, particularly against vulnerable populations who might be at greater risk of harm or have limited access to any benefits that may eventually arise from the research findings. The burden of participating in the research study should be more or less shared amongst those individuals and groups who are most likely to benefit from the study’s outcomes, such as receiving a newly approved treatment. This also acts as a way to verify that the study population is representative of the broader population with the condition being studied, ensuring that results will be generalizable and that they are not biased toward specific genetic makeups or subpopulations.

The role of the clinical research ethics board: IRBs and RECs

Third-party ethics boards known as Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or Research Ethics Committees (RECs, or Independent Ethics Committees, IECs) play a central role in safeguarding the rights and well-being of clinical research participants. The primary responsibility of these committees is to review research protocols to ensure strict compliance with ethical guidelines and regulations, focusing on the ethical treatment of human subjects as well as research integrity and quality.

Currently, any clinical research study funded by any US federal agency (such as the Department of Health and Human Services) or investigating an intervention involving a drug, device, or biologic, which is under the jurisdiction of the FDA, is subject to independent review by an IRB.[2]

However, this has not always been the case. The implementation of mandatory independent review of study protocols by IRBs in the US has a long history that dates back to the 1960s, when the director of the NIH James Shannon suggested that research involving human subjects could benefit from review by an impartial third-party to ensure ethical treatment of participants. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research was established by the US Congress in 1974, and later published the Belmont Report, which was incorporated into US regulations in 1981 and subsequently adopted by various federal agencies in 1991 under the Common Rule (US 45 CFR part 46 subpart A).

Ethics in clinical trials are enforced via IRB approvals and oversight through a few different angles, which we discuss below:

Protocol review

IRBs/RECs carefully assess clinical research protocols prior to the study beginning. This includes review of aspects of study design, wording of promotional materials, participant recruitment methods, informed consent procedures and forms, data collection processes, and review or conduct of a risk-benefit analysis. The IRB evaluates the protocol to assess whether the proposed study aligns with ethical principles of clinical research, and can deny the proposal and require the sponsor to make changes to certain aspects before the study is approved and can begin.

Participant protection

Participant protection is enforced by reviewing the informed consent processes to verify that it is sufficiently clear and thorough to enable individuals to make voluntary decisions about their participation based on accurate, truthful, and non-coercive information. The IRB also evaluates measures that the sponsors/investigators will take to mitigate risks to minimize potential harm to participants throughout the duration of the study.

Ongoing oversight

Ethical oversight by the IRB continues throughout the trial's duration with regular monitoring and periodic reviews conducted to assess participant safety and adherence to ethical principles and approved protocols on an ongoing basis. Monitoring may involve reviews of adverse event reports, mid-trial amendments to protocol, reconsenting, software and data collection systems, or other aspects of trial operations. If protocol deviations are identified, the study can be forced to stop or be put on hold until they are rectified and patient safety can again be assured. In case of severe deviations or noncompliance, studies can even be forced to terminate early.

Education and training

Beyond reviewing and approving protocols and conducting period reviews, IRBs can also provide guidance for sponsors/investigators regarding best practices for ethical conduct in clinical research studies. Some IRBs may offer education and training seminars or programs that help researchers gain a solid understanding of ethical guidelines so they can effectively navigate ethical aspects of clinical research protocol design.

Coordination with regulatory authorities

IRBs interact with regulatory authorities in various ways. For example, part of the IRB review process involves verifying compliance with FDA guidelines, and IRB approval and oversight of clinical studies is an important part of the process of FDA approval of an NDA application. FDA regulations largely define and mandate the roles and authorities of IRBs in terms of approving and denying trial protocols. IRBs may also provide input for developing new policies and guidelines, as they act as a sort of intermediary between regulatory agencies and trial sponsors and thus have a unique perspective on current issues in research ethics.

Implications of technological advancements and the future of clinical research ethics

As technological advancements continue to accelerate and these technologies are increasingly adopted in clinical research, there are several implications that can be anticipated (or which have already arisen) in relation to clinical research ethics:

Personalized medicine and genome sequencing

New medical technologies relating to personalized medicine based on individual genetic differences raises unique ethical questions regarding the privacy and sharing of this new type of personal health information. This type of data has a high potential for misuse as it can provide clues about individual susceptibility to various conditions. At the same time, it offers an extremely high resolution of insights that can allow for tailored therapies that are most likely to be effective on an individual basis. Data privacy considerations should be carefully considered alongside the general risks and benefits associated with genome sequencing and personalized medicine.

Increased data availability and privacy concerns

With the emergence of “big data,” referring to the enormous and ever-increasing amounts of health data currently available, there are concerns related to patient confidentiality and privacy, secure storage and transmission of such information, and fair usage. With technologies like wearable devices, fitness trackers, and sleep monitors recording personal health data on an ongoing basis from millions of people, there is a need for regulations on how this data can be shared and used in a way that respects patient privacy and is not intrusive or misleading.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML)

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are both being rapidly uptaken in clinical research, offering numerous benefits from faster trial design to automated data cleaning and even accelerated drug design. It is even becoming clear that AI algorithms may be able to make more accurate assessments of health data than experienced physicians. With this situation, there is a recognized need for strong regulations determining the directions of advances in these technologies, finding a balance between machine and human decision-making, potential limits on their use, etc.

Specific ethical concerns related to the use of AI algorithms/tools include transparency in decision-making processes and the potential for biases embedded within algorithms. Although they offer great potential for advancement across many aspects of clinical research, ethical considerations should be a critical focus of ongoing discussions to establish guidelines for the responsible and fair use of these tools within research involving human subjects.

Need for ongoing ethical training

In general, as the clinical research landscape evolves rapidly, the need for continued education and training on ethical principles among researchers will become increasingly relevant to ensure they are equipped to navigate emerging ethical challenges. Guidelines and regulations may be updated frequently, and as new technologies are widely integrated into workflows, periodic training and updates may be required in order to ensure that ethical standards can be upheld under the context of the increased sharing of data and interconnectivity of software systems and tools.

Conclusion

Ethics in clinical research are established and enforced through various guidelines designed to ensure the protection of participant rights and well-being and to maintain scientific integrity and public trust. Ethical considerations infiltrate all stages of research, from study design through to dissemination of results, and adherence to ethical guidelines in clinical research studies is verified through advance and periodic review by IRBs or RECs.

With a long history dotted by a few unfortunate instances of unethical treatment of human subjects (such as the Tuskegee study) and various landmark publications including the Belmont Report, the Declaration of Helsinki, the Common Rule (US 45 CFR part 46 subpart A), and the Nuremberg Code, the concept of clinical research ethics has evolved into the fairly sophisticated and controlled environment characteristic of today’s clinical research landscape.

As clinical research continues to advance and adopt new technologies, ethical research guidelines will need to continually adapt to ensure protection of patient safety and privacy in the midst of increased connectivity and data availability and sharing. In particular, the integration of AI and ML tools raises important questions about transparency and bias within algorithms and the fair and ethical use of these tools when it comes to the health of living human subjects.

Ultimately, maintaining a strict yet constantly evolving approach to ethics within clinical research is essential for ensuring participant safety, well-being, and privacy, as well as research quality and integrity.