Clinical Trial Site Selection: A Portfolio Management Approach for Diverse Recruitment

by Lauren Vamos, Operations Associate at Power

A major barrier to representative recruitment is the underlying diversity of the patient population at top-performing research sites. If the established patient population is not diverse then the site is unlikely to recruit diverse patients.

It may not come as a shock that historically preferred sites generally skew white and affluent. They’re often in higher socioeconomic urban centers, and are run by PIs at the head of their field. These clinics seem like a great first choice, but they are not the clinics to find representative populations.

So why don’t sponsors expand to newer sites to improve clinical trial diversity? New trial sites take 20-30% longer to start up. They need more oversight and training to effectively follow trial protocols and have more uncertainty about data quality and protocol adherence. It can also be complicated to navigate ethics review boards in new regions.

Expanding to new sites requires an investment that many sponsors and CROs are hesitant to make, especially if current sites produce reasonable results. As a result, the industry goes back to the same sites if they have a good track record, without incorporating diverse enrollment statistics into that track record.

It’s time to reframe site selection. Reorganizing site networks to optimize diverse recruitment doesn’t need to be difficult, time-consuming, or expensive. Before completing a feasibility questionnaire for site selection, let’s talk about portfolio management.

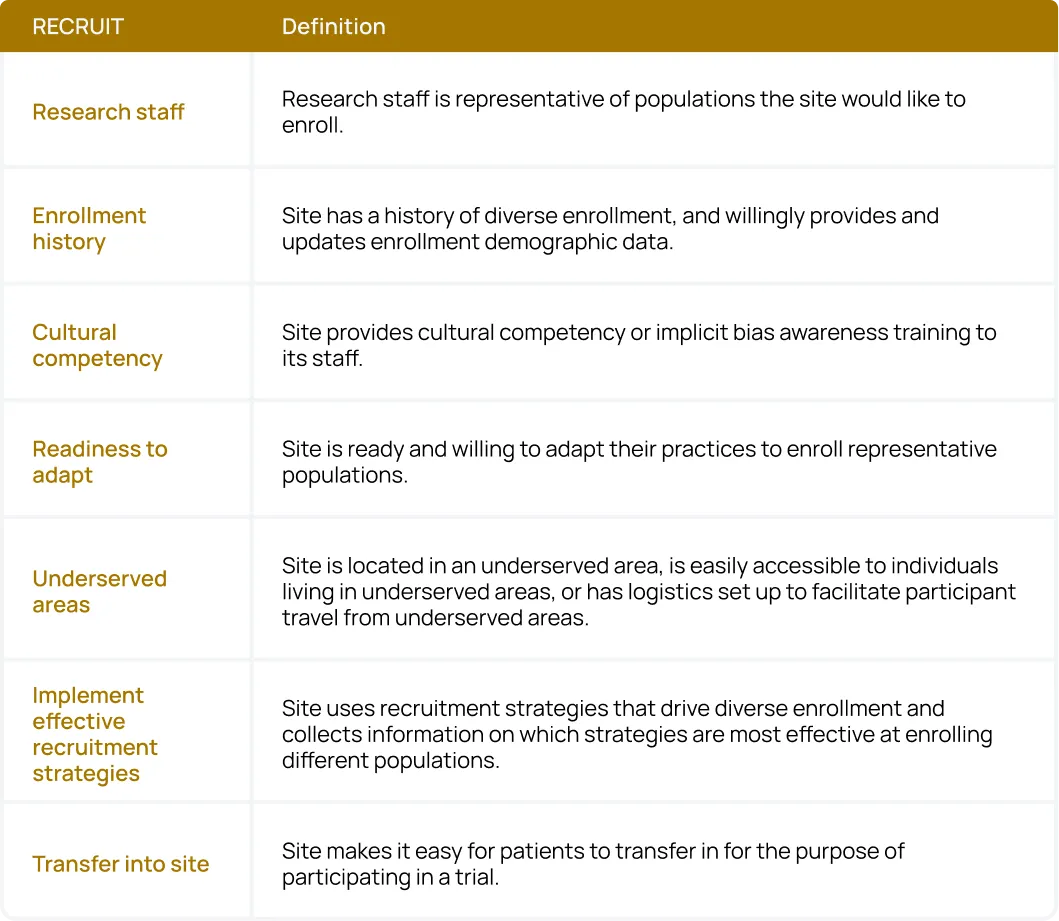

Sponsors and CROs can use the acronym RECRUIT as a checklist for their site network:

- Research staff: Research staff should be representative of populations the site would like to enroll.

- Enrollment history: Sites should have a history of diverse enrollment, and willingly provide and update enrollment demographic data.

- Cultural competency: Sites provide cultural competency or implicit bias awareness training to their staff.

- Readiness to adapt: Sites are ready and willing to adapt their practices to enroll representative populations.

- Underserved areas: Sites are located in an underserved area, are easily accessible to individuals living in underserved areas, or have logistics set up to facilitate participant travel from underserved areas.

- Implement effective recruitment strategies: Sites use recruitment strategies that drive diverse enrollment and collect information on which strategies are most effective at enrolling different populations.

- Transfer into the site: Sites make it easy for patients to transfer in to participate in a trial.

1. Research staff

A diverse research staff is crucial because sites with high staff diversity attract a more diverse patient population. One reason for this trend, according to Tufts University, is that participants are more likely to feel comfortable asking the necessary questions, and more likely to entrust their safety as research participants, to researchers who look like them.

Sites with diverse staff are also more likely to value diversity as a central part of their research, mission statements, and operating procedures. This trend means that sponsors and CROs will need to input less effort throughout the trial to ensure sites are recruiting representative populations.

The first step to optimize for diverse research staff is to collect data on two metrics: the demographics of site staff in your existing network, and the willingness of these sites to improve their diverse hiring practices in the future.

Frame this data collection process as a way of helping sites out: instead of setting hard requirements, provide sites with tools and training to hire diverse research staff. The second step is to ask new sites about their staff demographics upfront. Use this data as a primary deciding factor when expanding your site networks.

2. Enrollment History

There is currently a massive deficit in site-level demographic reporting. Sites do not generally provide data on the demographics of participants they’ve enrolled in the past. Often, they do not have this data available because it has never been required.

Sponsors and CROs should first define explicit performance indicators for each therapeutic area they are researching. Use census demographic data and morbidity statistics for the disease in question to determine these metrics. Depending on the disease and previous performance, you may choose to highlight metrics related to recruitment, enrollment, or randomization.

Once you have defined performance indicators, share these metrics with your existing site network and lead with the expectation that sites use these metrics to evaluate their own progress. Offer additional support to sites that are initially unable to meet these goals and frame the exercise as a method to improve clarity and communication between the site and sponsor.

Finally, sponsors and CROs should explicitly prioritize sites that share their defined metrics when building out a site network. Leading with this expectation will incentivize sites to begin collecting and proactively sharing data about their existing patient demographics.

3. Cultural Competency

According to one study, white coordinators and physicians feel uncomfortable discussing race and report feelings of anxiety when choosing the appropriate language to discuss inclusion in research. As a result, people from underrepresented groups are invited to participate in clinical trials at a lower rate.

Hiring diverse staff is an excellent first step, but it is also possible to train a less diverse site staff. There are abundant free, web-based implicit bias and cultural competency training options for site staff:

- Implicit bias training from the AAFP

- NetCE implicit bias training

- Think Cultural Health training from the Department of Health and Human Services

The first step is to provide these training resources to existing sites in your network. Next, sponsors & CROs can prioritize sites that have provided previous implicit bias training to their staff and shown improved results over time.

4. Readiness to Adapt

This metric is less about measuring and more about framing. Sites are generally doing the best they can with the resources they have and may be unhappy with a new slew of performance indicators and incentives.

The crucial element to highlight is an improvement over time. Not all sites will be able to hit diversity goals today, nor should they be expected to. But if sites capitalize on extra resources and think smartly about optimizing the tools they are given, they should naturally improve along these indicators over time.

If sponsors and CROs start collecting data and notice improvements along desired metrics, the site should stay. If there is no improvement, despite additional support and resources, then it might be time to re-evaluate the site’s inclusion in future research.

5. Underserved Areas

Underlying patient diversity at sites impacts their ability to recruit representative participants. Often, sites with the best track record for research are in less racialized, higher socioeconomic status (SES) areas. Internal physician referrals often drive patient recruitment, and these referrals pull from the established patient population.

Since people become patients at clinics in their neighborhoods, internal referrals will likely be less racialized and higher SES. Therefore, if the established patient population is not diverse, the site is unlikely to recruit diverse patients.

Step one to optimize site selection for existing patient populations is to use demographic data by ZIP code to highlight regions of interest for new sites. Requesting demographic data from sites will also help paint a picture of their predisposition for diverse recruitment. Regardless of external recruitment methods, a meaningful proportion of patients will likely come from internal physician referrals.

6. Implement effective recruitment strategies

CROs and sponsors should evaluate and prioritize sites that use representative recruitment strategies. If representatives do the upfront research to determine which site level vendors are primed to recruit diverse participants, it becomes easy to determine if sites are using the best tools available.

Researchers should prioritize default multilingual resources that contain representative imagery and adhere to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. They should also consider prioritizing sites that use patient education platforms like Power, disease-specific advocacy groups, and diverse patient support groups for recruitment.

7. Transfer into the site

If the established patients at traditional sites are not representative, then those sites need to make it easier for external patients to transfer in. Unfortunately, even if diverse patients are willing and able to transfer to active sites, they can still be blocked.

Large academic medical centers require participants to register as patients at the site before the screening. This process is often a large time and financial commitment, which is unattractive if patients have no guarantee that they will qualify.

If trials do not fund screening activities, insurance logistics can also be a barrier. There is less motivation to go through the insurance claims process if patients are not guaranteed access to the trial. Finally, without the use of sites like withpower.com, physicians at smaller community clinics may be less likely to know about trial options for their patients.

Consequently, the network of internally-referred patients skews toward patient populations in overserved regions. To combat this trend, sponsors and CROs should make ease of patient transfer an important site evaluation criterion. Metrics to evaluate this criterion include:

- Site ability to conduct a full screening visit before establishing the patient

- Site ability to run lab work out of patients’ local clinics where they have established insurance information.

Sponsors and CROs can also work with platforms like Power to help physicians identify and refer their patients to promising local trial sites that are easy for their patients to access.

Site Selection Leaders

Sponsors & CROs can establish & train a representative site network ahead of time to make study startup efficient. This process should include familiarization with new IRB processes at each site ahead of time. While marginally inconvenient, an early investment here can pay dividends down the road.

Some industry leaders have already begun the process of more thoughtful site expansion for diversity:

- PPD has recently started focusing its site recruitment efforts on community health clinics to recruit more diverse participants for their sponsors.

- Genentech has created a dedicated Site Alliance for diverse recruitment, which prioritizes sites where communities of color live and work, sites with a highly engaged investigator/coordinator community, and sites with a proven track record for diverse recruitment.

- MD Anderson partners with a variety of smaller hospitals like Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital. This partnership helps a greater range of people in the Houston area access MD Anderson research via their local institution.

Want to learn more about diverse recruitment? Download the full research report.