Attrition in Clinical Research

What does attrition mean in clinical research?

Attrition, in research, refers to participants who drop out of a clinical trial.

Attrition is a common problem in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and particularly in longitudinal studies that observe changes in subjects over time. Attrition results in incomplete or missing data for subjects, which can cause problems when it comes to analyzing trial data and interpreting study results. If attrition rates are different between treatment arms (more on this later), it results in attrition bias in a study.[2] In this article we will discuss reasons for attrition, how to calculate attrition rate, different types of attrition and why they matter, and a few strategies for preventing attrition (i.e., maximizing patient retention) in clinical trials.

What causes attrition? Reasons for attrition in clinical trials

There are multiple reasons why a clinical trial participant may drop out of a clinical trial, such as (but not limited to):[1],[3]

- A negative experience during the trial

- Feeling they weren't receiving adequate information about the clinical trial

- Finding the trial protocol too complicated to follow

- Fears about side effects, adverse reactions, or receiving placebo rather than treatment

- Difficult side effects, adverse reactions or death

- Transportation issues that prevent them from attending study visits or follow-up appointments

- Relocation to an extent that prevents them from actively participating

- Withdrawal of consent for personal reasons

- Lack of resources such as time or money

Lack of motivation, interest, or engagement

Attrition bias vs. random attrition definition

To better understand attrition, it is important to first distinguish between random attrition and systematic attrition, also known as attrition bias.

Random attrition occurs when the participants who drop out have roughly similar characteristics to those who remained in the study, and when there is no major difference in attrition rates or prognostic characteristics of those who dropped out between the different treatment arms in a controlled study. In other words, there is no identifiable unifying factor amongst the participants who were lost to follow up, nor anything that differentiates them notably from those who remained in the trial. Random attrition means that the approximations of sample similarity between treatment arms hold true despite the drop-outs. The statistical power of the study is thus maintained to some degree, although it is diminished due to the lower final sample size.

However, if the participants who leave differ significantly in some way from those who remain, or if attrition rates are dissimilar amongst treatment arms, that is known as systematic attrition, which is more commonly called attrition bias.[1],[3]

Why is attrition analysis important?

While it is clear that attrition reduces the overall sample size, it is important to further assess attrition in more detail, i.e., between study groups and in terms of the characteristics of those lost to follow up, in order to clarify whether any attrition bias exists.[4]

Giving a general definition for the extent of attrition that is likely to be problematic is challenging, because it depends highly on the specifics of the trial design and study sample. In general, it is considered that low attrition rates of ~5% are unlikely to lead to significant bias, while higher rates of 20% or more are likely to be worthy of further investigation to identify potential bias.[4],[5]

Analyzing attrition is important because attrition can lead to bias in study outcomes. Apart from the reduced sample size, which can decrease power and increase the likelihood of type II error, differential attrition (wherein attrition rates differ between treatment arms) can cause attrition bias, a type of bias that mimics sampling bias, wherein the baseline characteristics between treatment arms are not balanced.

Attrition bias should be analyzed to identify any potential effects on the internal and external validity of the study results. Internal validity concerns the relationship between the dependent and independent variables in the study, where differential attrition between treatment arms can skew results and introduce bias in the identification of any potential correlation.[1] External validity refers to how generalizable the study outcomes and results can be to the general population. Attrition bias can result in the final sample being less representative of the broader population, making it difficult to make the outcomes/results generalizable to underrepresented groups or to the general population.[1]

Failing to account for attrition bias in clinical trials can lead to misleading outcomes, may negatively affect perceptions of the trial, and may raise ethical concerns as to why patients are dropping out. Thus, analyzing attrition bias in research is a critical component of clinical trials in order to ensure validity and accurate interpretation of outcomes. It should be taken into consideration when making conclusions, and often it is important to explicitly report attrition bias and resultant effects in a study for the sake of transparency and ethics. Transparently reporting attrition rates and associated findings can also help fellow researchers design more resilient clinical trials.

What is attrition rate?

Attrition rate represents the number of participants that drop out or withdraw from a trial, given as a percentage of the total number of participants enrolled.

What is considered a "good" attrition rate in research?

Although it’s not possible to define an “acceptable” attrition rate applicable to all studies in general due to the extent of possible variation between unique studies, attrition rates of less than 5% are commonly considered acceptable and may not be a matter for concern. Attrition rates above 20% are more likely to lead to issues and have greater potential to impact the interpretation of study outcomes.[3],[6] However, these are just approximations; it’s possible for attrition rates even lower than 5% to cause statistically significant attrition bias, especially for small sample sizes or when the attrition is strongly differential between study arms.

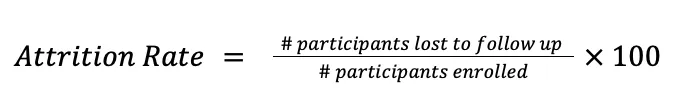

How to calculate attrition rate

Attrition rate is calculated by dividing the number of participants who are lost to follow up by the total number of participants enrolled at the beginning of the study, then multiplying by 100 to obtain the rate as a percentage, as shown below:

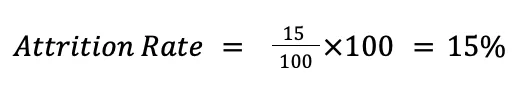

For example, in a clinical trial that originally enrolled 100 participants, 85 were left at the end of the study (15 were lost to follow up during the study, for various reasons). Therefore, the attrition rate for the trial is 15%:

How can attrition be prevented and mitigated?

To obtain valid results from a clinical trial as per its original design, sponsors and investigators should aim to minimize attrition. In other words, sponsors should make efforts to maximize patient retention. One way to go about this is to pay close attention to the reasons why participants are dropping out of the study, or why they have dropped out of similar prior studies. If it’s not possible to address these issues mid-trial, then changes can at least be incorporated into future trials right from the design stage to minimize attrition. You might like to check out our article dedicated to patient retention strategies for ideas in this regard.[7]

So, in terms of preventive measures, strategies to decrease attrition rates could include:

- Design patient-centric trials so your clinical trial is set up from the get-go to minimize the burden placed on patients. This is all about aiming to optimize the patient’s lived experience and has benefits not only for retention but also for enrollment and patient satisfaction. We have written an extensive article discussing patient centricity and another on patient-centric recruiting practices.[8],[9]

- Strong communication with trial participants has the potential to significantly reduce attrition in research studies. The more participants know about the study and feel connected to researchers, the more likely they are to stay in the trial until its completion. Further, being able to have any concerns or confusion addressed or clarified quickly may make the difference between a subject deciding to leave or to continue.

Sites or sponsors might choose to maintain open support channels open for participants, such as a phone line, email, online chat, or in-person support hours. Participants should feel welcome to voice their concerns, and offering anonymous feedback in the form of patient experience surveys or other formats could promote honesty.

- Offering flexibility in study visits and follow-up appointments can alleviate some of the logistical issues participants face, which are a common cause of attrition. By providing patients with different options for appointment times or enabling remote visits, they will be less likely to run into issues accommodating the trial visits in their busy lives. Minimizing the number of in-person visits required and scheduling them at reasonable intervals, where possible, also reduces the patient’s and decreases the chances they will get overwhelmed.[1]

- Over-enrollment is a potential strategy to use if high attrition seems inevitable for a study. Increasing the trial sample size beyond that which is needed for optimal power leaves some leeway and attempts to maintain the statistical validity of the results despite drop-outs. Recruiting more subjects than required can represent a significant increase in cost and start-up times, so this strategy should be used cautiously to prevent potential bias in results in trials for which high attrition rates appear to be inevitable.[1]

- Use automatic reminders to keep your participants engaged and aware of upcoming visits and data-collection points. Some participants may feel ashamed if they miss a visit or think that missing that visit disqualifies them, and then decide to simply stop responding or leave the trial. Automatic reminders can help avoid missed appointments, but it is also a good idea to follow-up quickly with those who do miss appointments to see if there is anything they need help with or any doubts they are having that could be rectified.

- Consider offering compensation to encourage participation, especially for clinical trials with more-demanding protocols. Compensation could take the form of cash, travel allowance, or reimbursements for study-related expenses. This can limit the influence of financial burden/financial anxiety on a patient's decision to stay in the trial.[1]

We should understand that even if a sponsor and sites take all of the aforementioned proactive measures to prevent participants from leaving a trial, some degree of attrition is simply inevitable in many cases. If you are dealing with an unexpectedly high attrition rate or a significant attrition bias in a given study, there are methods for mitigating the effects of the bias, at least partially, and accounting for it properly in order to maximize the validity of the study results based on the existing data.

Statistical techniques can be applied to the data, such as data replacement by regression, multiple imputation, standardized change scores, or endpoint analysis with regression, to attempt to reduce the effect of the missing data on the final results. However, applying only a single approach to the data might introduce another bias, so it is best practice to apply statistical operations with care, and perform multiple different analyses to properly assess the effects of attrition under the various assumptions/scenarios applied.[1],[5],[10] Collecting baseline data for patients, including various demographic and prognostic variables such as age, gender, ethnicity, lifestyle factors, etc., can be useful for later separating this data to separately characterize participants who completed the trial and those who were lost to follow up. Covariate analyses can then be considered when analyzing differential attrition data from these modified baseline tables.[5] At the very least, if the bias cannot be mitigated, it can be considered honestly in reporting the study results.

Conclusion

Attrition is common in clinical research, and has the potential to introduce bias and impact the external and internal validity of the study results. While attrition cannot be eliminated completely, investigators and trial sponsors have several strategies available for minimizing attrition (starting from trial design), and there are methods that can be used in some cases to attempt to account for and minimize the effects of attrition bias. Giving due attention to attrition and patient retention is important for maintaining the power of a clinical study and maximizing the generalizability of results and clinical outcomes.